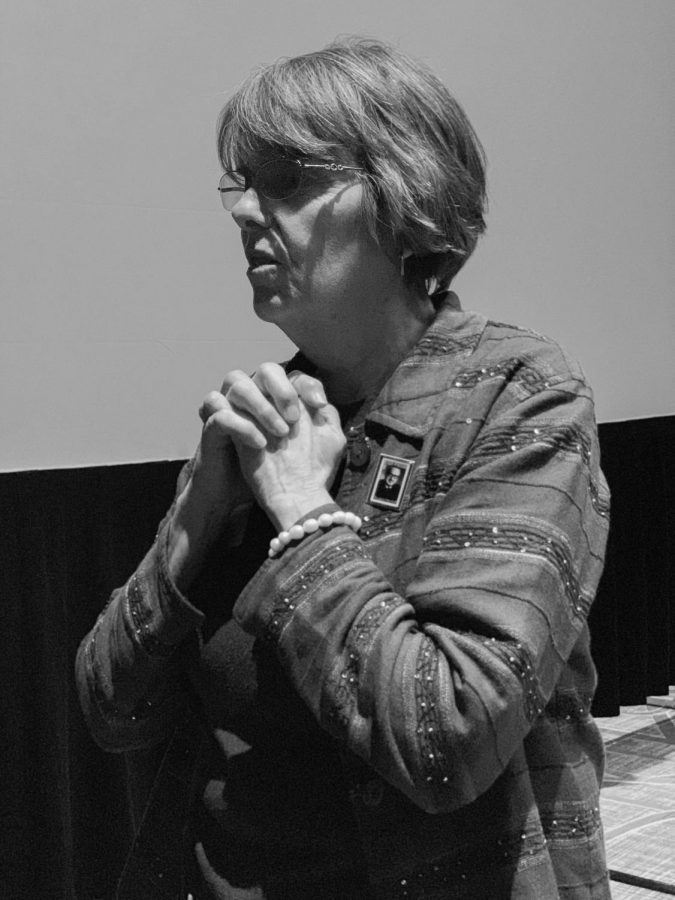

A conversation with Mary Beth Tinker

Tinker speaks with a student at the National Scholastic Press Association/ Journalism Education Association convention in Washington D.C.

December 26, 2019

Editors note: Mary Beth Tinker is known for landmark Supreme Court case Tinker vs. Des Moines, where the district was sued after suspending students, including Tinker, for wearing black armbrands protesting against the U.S.’s involvement in the Vietnam War. The Central Times’ Vivian Zhao and Amisha Sethi interviewed Tinker in light of a Naperville Central student’s racist Craiglist post that resulted in a hate crime charge and the district’s censorship of an October article.

This interview was edited for content, length and clarity.

Vivian: A student was charged with a hate crime after listing an African American student as a “slave for sale” on Craiglist.

Amisha : We’ve had a lot of racist social media posts and it is a pattern at our school. You would think once it happens once, and has very severe consequences, it wouldn’t repeat itself.

Mary Beth Tinker: It’s going to keep happening, especially in this climate that we’re living in right now, so much encouragement of hate speech and hate, and racism. Let’s call it what it is – racism. I really think every school needs to have an antiracism program curriculum, and the administration and the staff, the teachers need to work on this. You students should be part of it. In fact, you can call for it.

Every school starting around kindergarten or preschool should [have] a multicultural understanding – whatever you want to call it – basically to prevent racism. As a nurse, we like to prevent problems. Don’t deal with it after it’s already full raging.

Now, you’re at the point where you’ve already got a problem. I was in Illinois and a superintendent was there, and he said they have a really good program at one school called “critical issues class.’ And they talk about things like this, and he said [they’re] implementing this in every high school in [their] district. But the school should be held accountable, because school shouldn’t be like this for any kid.

I don’t think the students should just be punished too often. That’s what happens: the student does the racist things [is] just punished and excluded. That doesn’t really work. That can just backfire. Then the kid is alienated feels shamed; we don’t want to use shame. There’s plenty of racism to go around. It’s not like he’s the only one, and it comes out in subtle ways all the time. Maybe you could involve this kid in calling for some program at the school.

A girl at the school I was at held up her fingernails and said, ‘I have Confederate flags on all my fingernails!’ I was like, ‘Wait, kids, let’s not shame her, let’s not make fun of her, let’s talk to Jeanine. Jeanine, I’m so glad you said that and that you had the courage to stand up and say that. Let’s talk about why.’ Then get to talk to each other, to change [and] not just shame and punish.

A: But I also think that if the school were to, from the school’s perspective, if they weren’t to [discipline] the student, the community would be upset.

M: It can’t just be let go, but I’m just saying it’s not enough. Okay, duh, hello, we’ve got a problem here the school. We know it. It’s out there for everyone to see. What are we going to do so that the next kid doesn’t have to go through this? You are creative, you can develop curriculum.

In a speech at the National Scholastic Press Association’s fall convention, Tinker discussed implicit biases she held against her African American friend Valerie.

V: Part of your speech was about your participation in the civil rights movement and your experience with Valerie. A lot of our district’s focus is on implicit bias and being able to recognize that bias on your own. Can you tell me about your process with that?

M: Yes, I think it’s something that white people more and more need to take responsibility for. I’m in a reading group right now. It’s called “Showing Up for Racial Justice” and we read things like “Waking Up White,” Ta-Nehisi Coates’s article on reparations from The Atlantic, now I’m reading a book called “How To Be An Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi, which is also very good.

You can be a very nice person. Take care of your kids, love your neighbors, but you can still do things that are racist. Don’t be ashamed, it’s not just like you’re a horrible person. Let’s just get it out there in the open and talk about it. So I think it’s a responsibility, first of all, for all white people to work on. But I’ve also started to learn and realize that there are ways that people of color are racist towards people of color. Clarence Thomas has done some things that hurt black people in general [and] he’s black. It’s not just only white people that do things that are against people of color.

It’s a little bit complicated but it’s nothing that we can’t try to work on. The problem in our countries is that it’s just been swept under the rug.

A: Sharing your personal experience comes across as very honest because sometimes when people talk about these issues, it’s like, ‘Oh, I would never know.’

MB: As soon as you hear somebody say ‘I’m not a racist,’ you know they probably are. If you’re really not a racist, you’re going to acknowledge that ‘I probably am racist’ because I’m raised in this thoroughly racist culture. How are you going to avoid it? It’s like a fish in water.

V: I think the majority of our school isn’t racist, but some might still have implicit biases. What advice would you give students who want to overcome these biases?

M: Maybe you could do something like a school in Maryland did. They started a lunchtime program – I think it’s once every week or so – and students bring their lunch there and they talk about these things, and read about it and learn and raise [their] consciousness. If you want to be an engineer and you didn’t know much about engineering, you’d go to classes and learn. Let’s say you don’t really know a lot about racism, and why would we? We should have been taught about it since kindergarten.

So we have to learn from people who do know more about it. There’s plenty of resources out there right now.

There’s like 13,000 school boards in the United States. I think two have voting members that are students. The school board should have students voting.

A: What advice would you give people in addressing the issue of being discouraged about starting a conversation?

M: There’s a lot of discouragement out there, and I get discouraged as well. We can’t give up. I was reading this song from Leonard Cohen – don’t wait till things are perfect, just get started right now. Everything’s a little bit cracked, but that’s how the light gets in. There’s always some positive part.

A big part of what we do has to be keeping ourselves whole. A lot of this engagement helps that. That’s another reason why I travel around the country – when you speak up about something you care about, it feels very good.

V: Since you’re a nurse, but you’re also known for the Supreme Court case that drastically changed our free speech rights, can you tell us about how you applied that in your career outside journalism?

M: As a nurse, it’s so related. I took care of the kids and teenagers. I’d be taking care of a two-year-old had been burned in a house fire. My job is to unwrap the gauze, give them morphine, treat their burns, And I came to found out the leading cause of burns in children is housefires from slum landlords not keeping the apartment up to code. They’re making money off of some little child being burned.

I remember a boy who was about 12 years old, he’d been shot and blinded in one eye. The budget for the after school programs had been cut off. The poverty was contributing to all this because kids didn’t have somewhere to go after school. Putting it all together, and realizing that our case is really part of a children’s rights issue, a teenager’s rights issue, that’s really an international human rights issue. It’s about kids being a discriminated group and not having a voice to advocate for your own interests. Everybody needs to be able to advocate for your own interests.

You don’t have to get used to the mistreatment of young people living in these conditions where the climate is crashing and you’re getting asthma from polluters who are making money off the bad air, you’re getting shot because some organization bought off the congressman to vote for crummy gun laws that let everybody and their brother have a concealed weapon and an automatic gun. That’s not right. The war economy, that’s not good for kids.