During the 2022-23 school year, 23.5% of District 203 high school students were classified as chronically absent from school, based on Illinois Report Card data. A student is classified as chronically absent by the State of Illinois after missing 10% of school days, whether unexcused or excused.

Four years prior, during the 2018-19 school year, 14.45% of students across both District 203 high schools were chronically absent. The dramatic increase follows a national trend, with chronic absenteeism nearly doubling nationwide in a post COVID-19 pandemic world.

“We know that chronic absenteeism is not just a Naperville 203 issue,” said Chala Holland, Assistant Superintendent for Administrative Services in Naperville 203. “For districts across the country, especially coming out of the pandemic, it is one of the major areas that all districts have been impacted by.

How absenteeism is tracked

Naperville 203 submits a report monthly to the state with attendance numbers throughout the district from the month prior. In order to determine when a student is chronically absent at the high school level, the district divides the minutes present by the student over a denominator of the total time in the instructional day. The instructional time varies depending on the different lengths of school days.

For instance, school-wide late arrivals on Wednesdays and schedule choices like an early dismissal period both decrease the total instructional time. The ratio of time missed is then added to a student’s total, and when the student reaches 17.6 school days of missed instruction they are then classified as chronically absent.

Chronic truancy, defined as 5% or more school days missed while truant, is included in chronic absenteeism. When a student misses more than 50% of a period without an excuse, they are classified as truant. Between the two District 203 high schools, 3.75% of students are chronically truant.

According to a 2008 study by the University of Chicago, attendance and studying were found to be more predictive of dropout than test scores or other student characteristics. The study focused on examining Chicago Public Schools; where freshmen who missed more than two weeks of school flunked, on average, at least two classes. This study found that it did not matter whether they arrived at high school with top test scores or below-average scores.

“You cannot replace classroom time or face to face instruction,” said Mike Stock, a dean of students at Central. “Some of the informal curriculum, the interactions and the social settings is what kids need.”

At Central, Stock and his fellow deans, as well as nurses Erica Kelly and Alyssa Santella, are part of a professional learning community (PLC) tasked with addressing chronic absenteeism.

“We are helping to spearhead getting kids in and going back to their old habits,” Kelly said. “It was very easy to stay home during COVID because we were telling kids to do so. Now we’re just trying to shift that back to regular school attendance.”

The absenteeism PLC existed at Central prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but was put on the backburner during the pandemic for staff members to be reallocated to other PLCs.

Since the 2021-22 school year, Naperville North has had a 6% overall drop in chronic absenteeism while Central’s rose 1.6%.

During the 2022-23 school year, 40.9% of the senior class at Central was considered chronically absent.

How discipline works

Decisions for enforcing rules and practices around disciplinary measures for chronic absenteeism are handled on a case-by-case basis by the PLC, who run reports and check numbers of various students during weekly meetings.

“It’s a challenge to stay on top of all 2400 students,” Stock said. “There’s no siren that goes off on a Thursday afternoon, when little Billy is at 10 [absences].”

At Central, seven days missed in a class is a commonly-used metric where the PLC starts to take action. Contact is made with the student’s parents and teachers due to the increased likelihood of academically struggling in a class.

At 10 days, further contact may be made with parents to determine what may be preventing their student from showing up to class. The PLC then may try to take action to meet a student’s needs in order to ensure further attendance.

Beyond 10 absences, a stipulation may be put into place that a student cannot miss any more class without a doctor’s note for a valid excuse, Stock said.

The PLC also has a last resort option to try and limit absenteeism: if a student is “completely disengaged” with a class, they can be removed and placed into a study hall, Stock said.

Why students miss school

Reasons for chronic absenteeism vary, with no clear statistical data to point towards any one cause in District 203 specifically.

According to Attendance Works, a non-profit initiative to reduce chronic absenteeism nationwide, chronic absenteeism has many prominent causes including health problems, lack of safe or readily available transportation and food insecurity.

“There are so many reasons for our kids who are absent and we’ve not found a single one that’s the exact same,” Kelly said. “It’s an intense role that we have put ourselves in, because it takes a lot of investigation and just finding out and working alongside parents to figure out what the barrier is.”

Per Illinois law 105 ILCS 5, valid excuses for absence are illness, a doctor appointment, observance of a religious holiday, attendance at a civic event, a family emergency or other situations beyond the control of the student as determined by the board of education in each district, or other circumstances which cause reasonable concern to the parent for the mental, emotional or physical health or safety of the student.

“Almost every year we get a list of new exemptions for absences,” Holland said. “I’m not saying these aren’t valid reasons, but we know that students take mental health days. That was an addition of days off. We know that students can take it off for civic engagement. Those are additional days. At some point, our districts will have to stop and recalibrate what our attendance expectations are.”

Student Stories

Based on the last two years of Illinois Report Card data for District 203, the rate of chronic absenteeism inches up between grades 9 and 11, before skyrocketing in grade 12. At Central during the 2022-23 school year, there was a 16.5 percentage point difference between the senior and the junior classes rates of absenteeism.

“I think there’s a school culture or norm where seniors are not expected to try as hard in their classes,” senior Tony St. John said. “There’s more of a focus sophomore and junior year to work hard in the classes and get the stuff done. Especially for me, that was the way it went. I worked really hard last year and junior year, and now that I’ve selected a college it’s not as important to me, to be in class as often and get as high a grade.”

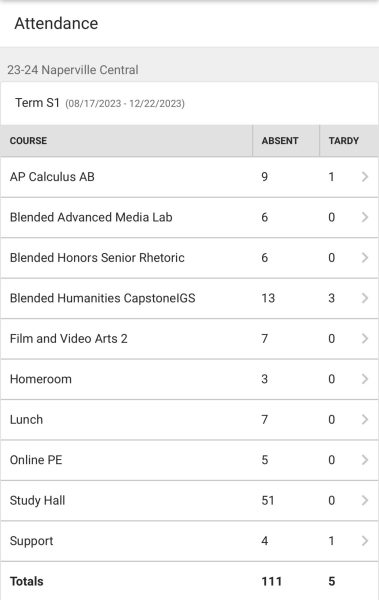

St. John is on track to be classified as chronically absent this year, with 108 missed periods according to the Infinite Campus portal at the time of an interview.

“I get sick very often and end up having to just call out for one or two days,” St. John said. “I try to maximize my time in school, but sometimes I’ve got a fever. I can’t even learn so I’ll go home and just try and get better.”

In the second week of school, St. John caught COVID-19 and promptly missed five days while recovering from the virus. Two weeks later, he got sick again and further missed school. St. John has not heard any communication from a member of Student Services so far this year regarding absenteeism, though in several of his classes his absences total over 13 missed days. In addition, neither he nor his parents have sent a doctor’s note to the school.

If a doctor’s note is sent to school while a student is recovering from illness, the absences do not count towards any form of further investigation by members of Student Services for chronic absenteeism, Kelly said.

“I have anemia, so sometimes I just know I won’t be able to get through the day without passing out,” said Penny Geno, a junior at Central. “I’d rather not do that, so I stay home and do my work.”

Geno has 70 absences so far, mostly related to her illness.

“I’m definitely behind in all my classes, and it’s just really hard to stay up to pace with everyone else,” Geno said. “It sucks, but there’s not much I can really do about it.”

Senior year brings along a bevy of reasons for increased absences. Whether it be senior skip days, college application procrastination or general bouts of Senioritis, a coined term for senior burnout, reasons vary across every senior class.

“I had to take like two days off of school to work on college [applications] and then got sick also,” senior Faiz Muhammad said. “A few days I was absent, it was just because I didn’t feel like it. But it’s not a great excuse.”

Muhammad currently has 57 absences this year and his parents normally call him out when he asks them to.

“They already trust me,” Muhammad said. “I think I also trust myself to catch up on most of the work that I still have to do. I think for the majority of classes, though, I would say that I’ve been more productive outside of class instead of actually just being in class, because a lot of times that stuff we do in class, I feel like I can just kind of do it on my own.”

Senior Kaushik Srinivasan has racked up 90 absences so far this semester. Seven of his classes have passed the 10 absence mark. He has primarily missed due to college applications.

“I think it kind of was like a cycle where I would be absent,” Srinivasan said. “I would get all my college apps stuff done for that day. But then I would just have a bunch of homework. So I’d be up late. And then the next day, I would also take an absence because I was up late.”

In the classroom

“Every student that I’ve had that is chronically absent, they’ve been totally fine,” said Michael Wilson, a social studies teacher at Central. “We’re talking like A’s and B’s. It’s something that I’ve never been super concerned with because they were academically getting everything that I was asking other students to do while being there like a fraction of the time.”

Wilson may be regarded as unorthodox compared to traditional ideologies about the importance of showing up to class.

“I will deflect to the district’s goal and that’s for students to be meeting the standards of their academic classes,” Wilson said. “If that’s happening, I don’t see the problem [with missing class]. I’m also the first person to tell you that the most important thing any student’s getting here is social emotional growth, the ability to work with others, seeing people from different walks of life, because you’re not going to remember the academic standards you meet two years from now.”

The feelings shared by Wilson represent a broader spectrum of opinions in the educational space of how much of an effect chronic absenteeism has on the classroom.

I struggle to believe that a student who’s sitting at home in their bedroom, knocking stuff out and not engaging in any of the classroom discussions and interactions, quality face to face teaching, plus whatever extracurriculars we have available, is in a situation best for any student,” Stock said.

Blended classes have brought a new education model to the forefront in recent years. In these classes a portion of the week is dedicated to independent instruction, where the student can work online from an alternate location independently.

“More students are taking blended classes, and I think they might be applying that same type of logic to non blended classes,” math teacher Nick Straka said. “They think, ‘this is not a critical day, I can miss this day and be fine.’ I don’t know how much that online learning environment from COVID contributed to that attitude. But it certainly seems, anecdotally, that it did increase right after that.”

Straka has observed that in his two multivariable calculus classes (MVC), which are filled mostly by seniors, that absenteeism increases during class periods with no direct instruction or quizzes.

“I just don’t remember ever seeing kids getting called out so frequently,” Straka said. “You’d have absences, but you wouldn’t have the frequency.”

In addition to MVC, Straka teaches Differential Equations, where students are 3 years ahead of their grade level track for math. Students are two years ahead in MVC. In Differential Equations, the small class of 10 people can have an even greater impact on instruction when students miss class, Straka said.

“I don’t think a lot of students, especially in the higher honors level classes, value things that aren’t grade based,” Straka said.

English teacher Taylor Heatherly only teaches senior-level blended classes, not including homeroom and a supervision period.

“I think that [students ask] a healthy question of, ‘well, why?,’” Heatherly said. “‘Why are we learning this?’ And number two, ‘why are we learning it in this format?’ And three, ‘what is better for me holistically: mentally, emotionally and socially?’ I think students are getting better at knowing what’s better for them mentally and emotionally. But I think that they’re not giving credence and respect to teachers who might know what they need socially.”

The future

In Naperville 203’s Strategic Blueprint, the district outlines a broad plan for growth from 2022-2027. Under “Strategic Focus 1,” they outline two goals that relate the school day structure: “Conduct an analysis of innovative school day models that support effective MTSS [Multi-Tiered Support Systems] and flexible use of time and space that responds to the student of the future,” and “Design and implement relevant, high quality learning models that foster personalized environments to meet diverse students’ interests and needs through blended and online learning structures.”

“Our absenteeism data is also telling us that time to change,” Holland said. “Students want educational experiences for themselves. The district is seeing an increase in early graduate positions, requests for students to have abbreviated days, to have different work experiences, internship experiences, or to do other things. We need to reevaluate. Our students are telling us something. Senior year, quite frankly, I believe needs to be rethought.”

The problem isn’t with just seniors though: While they make up a vast percentage of chronically absent students, across all grades absenteeism has seen an increase in recent years.

“When a place has expectations and they’re clear, we should be holding people accountable,” Holland said. “That’s all stakeholder groups, whether a parent calls the student out, or a parent never picks up the phone and never calls their kid out, we’re all responsible.”

At Central, Stock cites an example of a video sent home to families in which attendance was emphasized as an example of how they’ve tried to reach out to community members regarding being present at school.

“I love kids who are involved in extracurriculars, you know, who have goals, ideas, and interest beyond grades,” Stock said. “That’s something that we want kids to have for the rest of their life. We have to make this place of value.”

SM • Sep 27, 2024 at 5:21 pm

To the students with severe medical conditions who have been harassed and threatened with disciplinary action, you have my condolences. Your life means more than grades and their metrics.