When detentions don’t work: For some chronically truant students, detention never ends

March 13, 2023

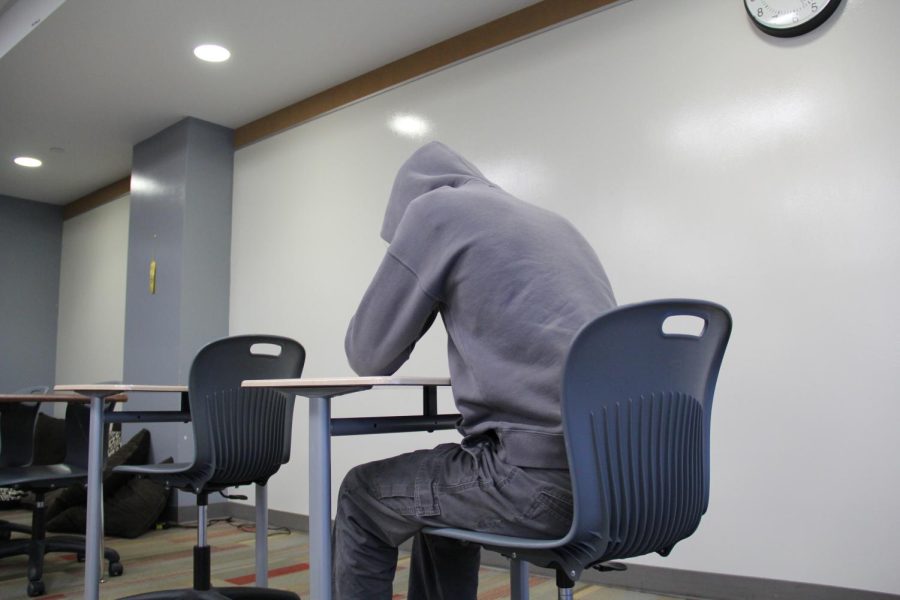

From 8 a.m. to noon on almost every Saturday he can remember, senior Patrick Geiger sits in Room 101 for detention. The supervisors won’t let him speak to other students or sleep, but he tries anyway. He’s supposed to study and get work done, but as one sophomore serving detention with Geiger said, most people just “stare at the wall.”

Geiger is in detention because he’s been truant for 224 periods and tardy 107 times this year.

“It’s just Saturday after Saturday after Saturday after Saturday after Saturday,” he said.

Geiger said the sheer number of detentions is proof the punishment isn’t effective.

“[It isn’t] working because it’s a punishment instead of [asking] ‘what could we do to help,’” he said.

Geiger said he’s usually late to class because he just doesn’t find his first period PE class important.

“I’m not too motivated to come to first period gym class just to stand around with all those kids,” he said. “During weekdays, I usually play until two or three [in the morning].”

Normally, he gets four to five hours of sleep a day. The night before his Saturday detention, he slept for one, he said while yawning.

But why does he get so little sleep? What could the school do to help him get to class on time?

“I don’t know,” Geiger said.

Nine out of 10 times, consequences like an after-school detention, a Saturday detention or a meeting with a dean solve the attendance issue, dean Jennifer Prerost said.

“[But], we will have that one [student] out of 10 where the consequences aren’t changing the behavior,” she said.

According to Prerost, deans will take time to communicate with students and parents to try to address the root cause of the issue.

“What would help change those behaviors?” Prerost said. “I would love [it] if the students could say ‘hey, this is why I’m truant.’ Oftentimes, [however], I think those students that are chronically [truant] don’t know either and aren’t sure how to solve the problem.”

Cases like Geiger’s are a minority, according to Prerost, but he’s not the only student with excessive tardies or truancies who isn’t fazed by detentions.

Sophomore Jaden Martinez served a three-hour detention with Geiger on Feb. 6 for missing a support period his teacher assigned him.

“Sometimes I just don’t like to go to class,” Martinez said. “[I got a] detention today, [but] of course [I’ll continue to be] tardy because I don’t think it’s affecting anyone besides me. I have all A’s and B’s. I don’t think I’m missing a whole lot in the first few minutes of class, and I’m just gonna live with that consequence of being late.”

Instead of going to class some days, Martinez prefers to spend time in the lunchroom or hallways with friends.

“I just feel better when I’m with my friends and I don’t really have a break in my day,” he said. “And I’m waiting all the way till sixth period [lunch] to be able to socialize with my friends. Sometimes, I just like taking my time in the hallways.”

But whatever the reason, Martinez and Geiger are both often tardy and truant, for which both are punished. Yet, the detentions they rack up aren’t deterring them.

“It’s disheartening for me personally when I feel like I’m not getting anywhere with a student or a family,” Prerost said. “I don’t want to assign detentions, but I’m not sure what the other recourse is.”

This year, District 203 hired two student advocacy specialists at Central and opened the Community Resource Center (CRC) in Room 38, which now holds in-school suspensions. It’s also open during lunch periods as a place students can find a sense of belonging, Prerost said.

While students are not suspended for being chronically truant or tardy, if they fail to serve a four-hour Saturday detention, they are assigned an in-school suspension in the CRC. There, student advisory specialists will open a discussion with the student.

“We’ll talk about what happened,” student advocacy specialist Ryan Crawford said. “‘What were you thinking at the time?’ ‘Who was impacted?’ And the big question is ‘what do you feel like needs to happen to make things better?’ We use those questions to guide our intervention.”

Through “restorative conversations,” student advocacy specialists work to change student behavior, student advocacy specialist Rebecca Moss said.

“Our intervention comes into play when we’re providing intentional and explicit instruction to combat those behaviors,” Moss said. “We really talk through the incident. That way we can better guide and support them so that we can minimize those behaviors from repeating or decrease them altogether.”

Lani R • Apr 25, 2023 at 11:38 pm

This is exactly why detention doesn’t really do any effect. I know some people that don’t get the point of detention and just don’t really care. All they do is sit in a silent room. What good is that going to do for their future really??

Linda McShrawn • Mar 14, 2023 at 10:42 am

It’s sad to see the American school system failing young adults who could be using their time for more important activities. The district gives detention after detention to these students, yet they continue to skip class or arrive late. As a mother of two, I am simply repulsed by the fact that the school acknowledges the fact that there is a problem but continues to administer the same punishment over and over with little effect. Do they not realize something might be wrong with the system?