COVID-19: A year later

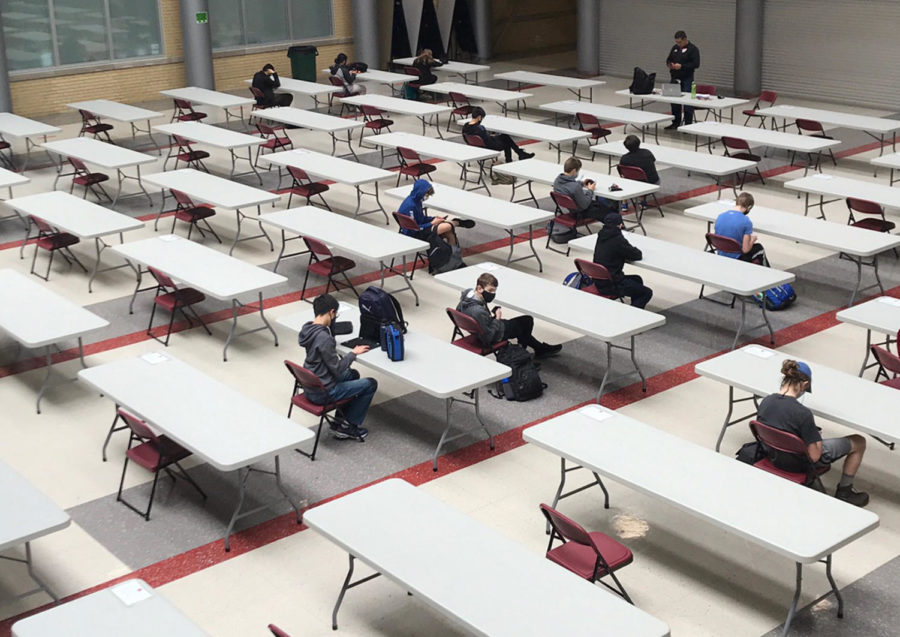

Masked hybrid learning students sit socially distanced in the cafeteria during free periods.

April 22, 2021

A year and a month ago, the world went into lockdown as the first major pandemic in a century swept across the globe. Streets were dead and stores were empty, everything froze in silence as if it were abandoned. Nobody knew what to do, and everyone was in shock as the unprecedented situation developed.

Last March, Central Times published an article titled “As coronavirus spreads, so do misconceptions,” in which experts told Central Times that the virus would have a very little effect on Americans, who had little to worry about.

On Friday, March 13, 2020, Naperville Central students found out that they would be heading home from school early on an extended spring break, expecting to return shortly after. Students cheered and celebrated during the passing periods, everyone shouting and happy to get their extra long break.

“At that time, I fully assumed we would be back in school in person as soon as spring break ended,” superintendent Dan Bridges said. “Then as we started to learn more about the pandemic and how it was impacting us globally, it became a lot more personal in terms of concern for what it was going to do to us.”

Assistant Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University Judd Hultquist spoke to Central Times with the initial conclusion that “the likelihood is almost zero that the infection will take hold here in the U.S..”

But after living with the challenge for more than a year in the states, it is clear that it did take hold, and tightly.

Hultquist has a background in virology, qualifying him to make predictions regarding the virus at this time. Experts couldn’t be blamed for being mistaken. “We were making assumptions based on other coronaviruses, such as MERS,” Hultquist said. “[Other coronaviruses] always were not transmissible unless somebody was showing symptoms.”

As is common knowledge now, however, asymptomatic transmission is one of the ways that COVID-19 is able to spread so easily and silently.

While scientists continued to study the virus and its nuances that were unknown, the general public was left in the dark for some time, and told to quarantine in total lockdown.

“At the very beginning, when people were first going into lockdown through roughly the end of May, I was actually very impressed with the general public’s willingness to upend their lives for each other on the basis of this important public health and scientific advice,” Hultquist said.

Everyone waited at home and the world seemed to stop.

“Everything was bizarre,” Naperville parent Amy Scott said. “It was like we were living in the book ‘Life as We Knew it.’”

People washed groceries with bleach and avoided each other as if even eye contact was dangerous.

“I remember running on the riverwalk,” Scott said. “There was a family of like four people. And as soon as I ran past, they saw me coming and they all turned the other way.”

Nobody knew quite how to react in the beginning. Eventually though, society had to begin moving forward. The world couldn’t afford to keep existing in a static state with nothing to keep society running.

For students and Bridges alike, a return to school was first on their minds.

“Right away, the team started to identify a number of ways we could change instructional practices,” Bridges said. “Knowing that we’re going to have to do things differently for different populations of kids.”

Within the two weeks since the abrupt departure from school, a new plan for online learning was in place.

“I’m extremely proud of the work that our team has done, and the creativity and the innovation that they showed to try to respond to this pandemic,” Bridges said.

As students, schools and the general public have trudged on through the pandemic, a light at the end of the tunnel is finally within reach.

The first vaccine made its debut into the general public in early 2021, finally signaling that the end may be closer. As of April 12, the vaccine has become available to all individuals 16 and over in the state of Illinois.

That doesn’t mean COVID-19 will be gone for good once the vaccine is distributed. Other variants and mutations will likely continue to arise.

“We don’t have any variants that are circulating currently that can completely avoid the vaccine,” Hultquist said. “The fear is that this steady drip of mutations will eventually create a virus that will be resistant to the antibodies that we get from the current vaccine.”

Mutations in the virus is what can cause a vaccine to become less effective as the disease grows and changes in ways to get around vaccine antibodies.

“So far it looks more like it’s going to become an endemic virus,” Hultquist said.

An endemic virus is one like influenza, where each year there are new strains and viruses that coalesce and scientists must adapt vaccines each year to treat them. So just like influenza, 100 years earlier, while the large pandemic is gone, society will likely be fighting COVID-19 continuously for a long time, just more routinely.

For the near future however, the vaccine poses excellent chances of easing the struggle against COVID-19.

“Everyone went through a traumatic event,” Scott said. “We’re all going to react differently and come out of this differently, and I think it’s going to take a while for our brains to heal.”