New Illinois bill would require parent or social worker’s presence when students questioned about potential crime

March 19, 2019

Two years ago, Naperville North student Corey Walgren died by suicide after being questioned by school officials and police over allegations of misconduct. Now, teenagers in the community are looking to make a change.

Rekha Iyer is a Neuqua Valley High School student who is a part of IlI. State Representative Stephanie Kifowit’s Youth Citizen Advisory Council. Iyer and the Youth Council have been crafting a bill that would call for a parent or mental health professional to be present when a student is being questioned about a crime by school administrators or law enforcement.

“School children who don’t fully understand the criminal justice system or the consequences of certain actions deserve to have someone looking out for their best interest during police or authority questioning,” Kifowit said in a news release. “This bill doesn’t take away a school’s or law enforcement’s ability to thoroughly investigate students’ behavior. Rather, it puts in place a safeguard to mitigate students’ emotional distress and prevent self-harm as law enforcement does their job.”

In an interview with the Naperville Sun, Iyer said research she conducted shows outcomes are better in schools that implemented a process where a parent, guidance counselor or social worker is on hand. She further said she learned the process reduces the number of out-of-school suspensions because there is a team-approach to determining the consequences.

While Naperville Central dean Kathy Howat said they do value the “team approach” at Central, there is no policy that explicitly states how and when parents become involved when students are questioned by the administration.

“We try to involve parents as much as possible but if I had to call a parent down quite honestly every time I talk to a kid about a tardy or truancy it wouldn’t be time effective,” Dean of Students Kathy Howat said.

For more serious allegations, the deans like to involve the parents, but it is not always right away.

“No, [parents] don’t have to be present and typically we find out what is what first,” Howat said. “Let’s say that that we got a tip that somebody had drugs on them at school. We don’t know if it’s true but it’s certainly something we would want to investigate because we don’t want kids to have drugs at school. So [we] get the student down here and [talk with them]. We do call parents and say ‘Hey we had this interaction with your kid. Do you have any red flags about this? Is there more to this story that we should team on for the safety of your of your student?’”

However, because the child has already been talked to by the dean alone, they may already be at risk for abnormal behavior. Kifowit says this is why it is so important for a parent to be apart of the questioning with students to mediate.

“It is extreme,” Kifowit said about the case of Walgren’s death in an interview with the Daily Herald. “But then it makes you extrapolate and think about what we don’t know, like what kids are harboring depression from an interaction, or what other situations are causing great distress.”

Junior Bella Montgomery was talked to by a dean last year for a school dress code violation.

“No, they didn’t [make me aware of my rights],” Montgomery said.

Montgomery thinks the situation would have gone better had her parents been present when she was talked to by her dean.

“I feel like it could have been nice because there would be another person there to back up my character, you know?” Montgomery said.

Despite this, Howat does not see the need for a change in Central’s policies.

“I feel like we involve parents and team with them and I feel like our current practices are good,” Howat said.

At Central, students do have the right to refuse to talk to a dean until their parents get there.

“We’d be wasting a lot of people’s time, but we can’t force anybody to say anything,” Howat said.

If a student were to refuse to talk to a dean until his/her parents arrived they would not be permitted to continue learning.

“They would probably have to go to the in-school [suspension] room where they were supervised,” Howat said. “I don’t know if that’s considered a punishment or not.”

Deans at Central do not explicitly tell students their rights before they question them.

“We might not say, ‘OK I’m going to talk to you… this is your due process. Do you know what that means? Do you know what I saying?” Howat said. “But we typically [say], ‘Hey, we’ve got some questions for you.’”

Should Kifowit’s bill become law all Illinois schools would have to comply with the new procedures or face legal ramifications. Kifowit hopes this bill will help students safety at school.

“The mental health of our students is an issue that I take very seriously,” Kifowit said. “I appreciate the support from members of my Youth Advisory Council on this measure and others that we are working on to increase students’ access to mental health services and make sure they receive proper support.”

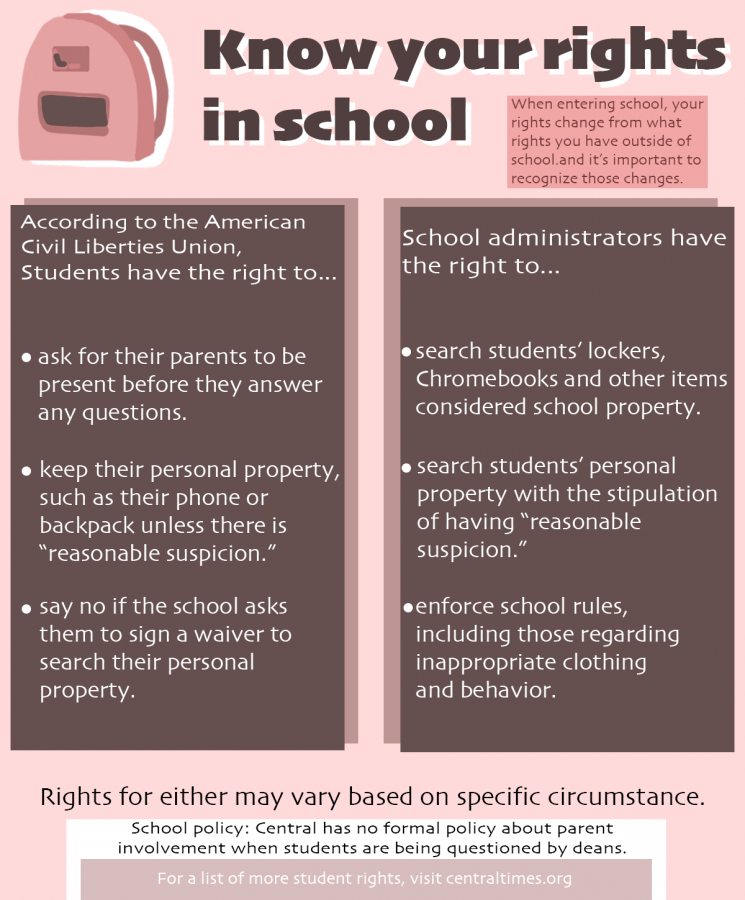

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS

-

Can only suspend you after other interventions fail, unless your behavior is serious, violent, or dangerous to others.

-

You have the right to tell your side of the story and present evidence in the conference with the school administration before you are suspended.

-

Public schools cannot require you to waive your right to privacy in order to attend school

-

You have the right to keep your personal property including but not limited to phones and backpacks unless there is “reasonable suspicion.”

-

“reasonable suspicion” must be based on facts and not merely on rumors, hunches, or curiosity

-

If you are being questioned by a police officer at school you must be read your rights

-

You can say no if the school asks you to sign a waiver to search your personal property

-

You do not have the right to a parent when being questioned

-

Central has no policy about parent involvement when students are being questioned by deans