Education with discrimination: Baha’i seniors denied studies beyond high school

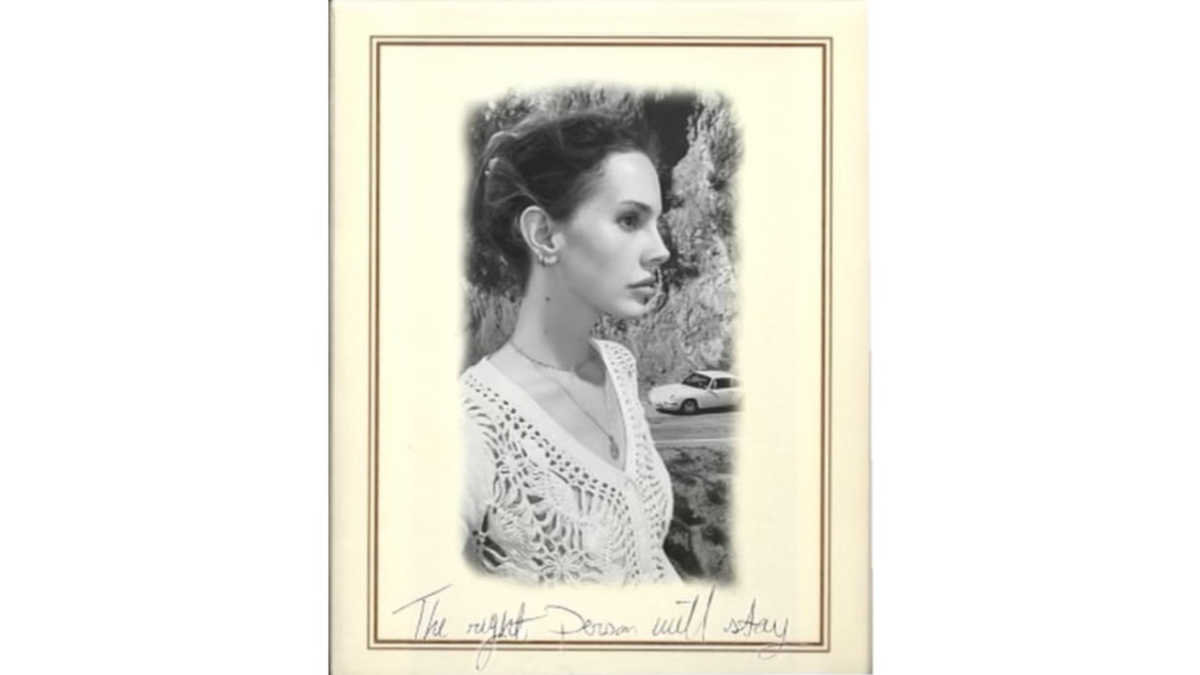

Mehry (left) and Mozhdeh (right) Khodarahmi were denied education beyond high school in Iran. They moved to the U.S. and were able to pursue their educational dreams. “We worked hard and having the freedom to work hard is a blessing,” Mozdeh said.

January 13, 2018

In high schools 6,502 miles away, Iranian seniors who belong to the Baha’i faith are faced with very different opportunities than seniors here. While their classmates apply to universities, Baha’i youth in Iran are denied the right to higher education solely because of their religion.

Since the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, a minority religion called the Baha’i faith has been discriminated against and members of the religion are unable to receive college education.

By denying them access to higher education, the Iranian government hopes to place members of the Baha’i faith at an economic and social disadvantage. Even today, Baha’i high school seniors have very few educational options after high school.

Mehry Khodarahmi, a Baha’i from Iran, immigrated to Naperville in 1999. She was denied the right to education after she graduated high school.

“Stopping education was one of the ways that they decided to ruin the hopes and dreams of all the youth and of the whole community,” Khodarahmi said.

While sitting in her second grade classroom, Mehry heard the Islamic revolution starting in Iran.

“Outside of my school people were running around burning tires and cars and we could hear people shooting,” Khodarahmi said. “That was the start of the whole plan to stop Baha’is and to burn their dreams.”

Mehry’s younger sister, Mozhdeh, left Iran in 2007 and joined Mehry in Naperville. When living in Iran, Mozhdeh faced discrimination against her religious beliefs.

“The government confiscated everything and the secret service was always around,” Mozhdeh said.

In Iran, high school seniors take a college entrance exam similar to our SAT or ACT. However, Baha’i youth are not allowed to take the college entrance exam which prevents them from attending Iranian universities.

“Bahais continued going to take their college entrance test and they were denied,” Mehry said. “At the start of the revolution, they started adding one line to all of the applications- your religion.”

If a Baha’i asks why they can’t take the test, the test administrator tells them that it is because they are a Baha’i, but never gave them a written reason.

“Education was a part of the whole campaign that the government had to stop and limit the Baha’i faith and the Baha’is who were living in Iran,” Mozhdeh said.

In 1987, the Baha’i community developed an alternative pathway to higher education that circumvented anti-Baha’i restrictions. They began to secretly educate their youth through an “underground university” called the Baha’i Institute of Higher Education (BIHE).

To this day, Baha’is in Iran are not allowed to gather in groups of more than 15. Consequently, the BIHE is unable to teach using traditional classrooms. Students complete work in private homes or basements and turn it in to be graded by teachers, many of whom were fired from Iranian universities.

As the BIHE began to produce well educated Baha’i youth, the Iranian government began arresting teachers.

Mozhdeh explained that the government intermittently arrested teachers in order to create a sense of fear within the Baha’i community.

The BIHE is much smaller today, but it still exists.

There is a lack of widespread understanding of the scope of this crisis due to government intimidation and jailing of anyone who publicly promotes or supports the Baha’i faith in contradiction to government wishes. There are currently 97 Baha’is in jail, many of them are Iranian journalists.

Sanctions from other countries have been ineffective at convincing the government of Iran to allow members of the Baha’i faith equal rights. The government continues to deny these violations, which continue to this day.

The Iranian government has been successful at concealing the extent of their religious discrimination by publicising lists of Baha’is permitted to enroll in universities, only to later expel them prior to graduation.

Mozhdeh and Mehry explained that the charges for every Baha’i who is fired from their job, expelled from school, or put in jail is the exact same. Each one of them is accused of being a spy for other countries.

Rashmi Kumar, a senior at Naperville Central, has never heard about these acts of religious discrimination in Iran and believes that this discrimination is extremely unfair.

“I don’t really understand why religion and culture should dictate whether or not a certain person should be able to receive an education, especially in this day and age,” Kumar said. “Everyone should be able to choose the path they want to take in life.

International Baha’is attempt to raise awareness of this important issue.

According to an article on the Baha’i International Community webpage about Iranian Baha’is, government-led attacks on the country’s largest non-Muslim religious minority have re-intensified over the last 12 years. Since 2005, more than 1000 Baha’is have been arrested, and the number of Baha’is in prison has risen from fewer than five to more than 100 at one point.

Mehry left Iran in 1999 and Mozhdeh left in 2007 to escape religious persecution.

They both continued their education when they moved to the United States. Mehry has received her undergraduate degree from Northcentral University, her Associates degree from the College of DuPage (COD), her Master’s degree from Northcentral University and is currently studying to earn a Master’s degree in business and accounting.

Mozhdeh earned her Bachelor’s degree from BIHE, associates degree from COD and her Master’s degree from Northcentral University.

Being able to attend college after growing up knowing they had few options for education in Iran brings them both great joy.

“The fact that I can go to school, sit in a class, and there is a teacher,” Mehry said. “And she is explaining this book that I am supposed to read. That is a blessing. It is something that we were so deprived of.”

Mozhdeh agrees.

“We worked hard and having the freedom to work hard is a blessing.”